Yasmin Essafi, La Lucha, 2024

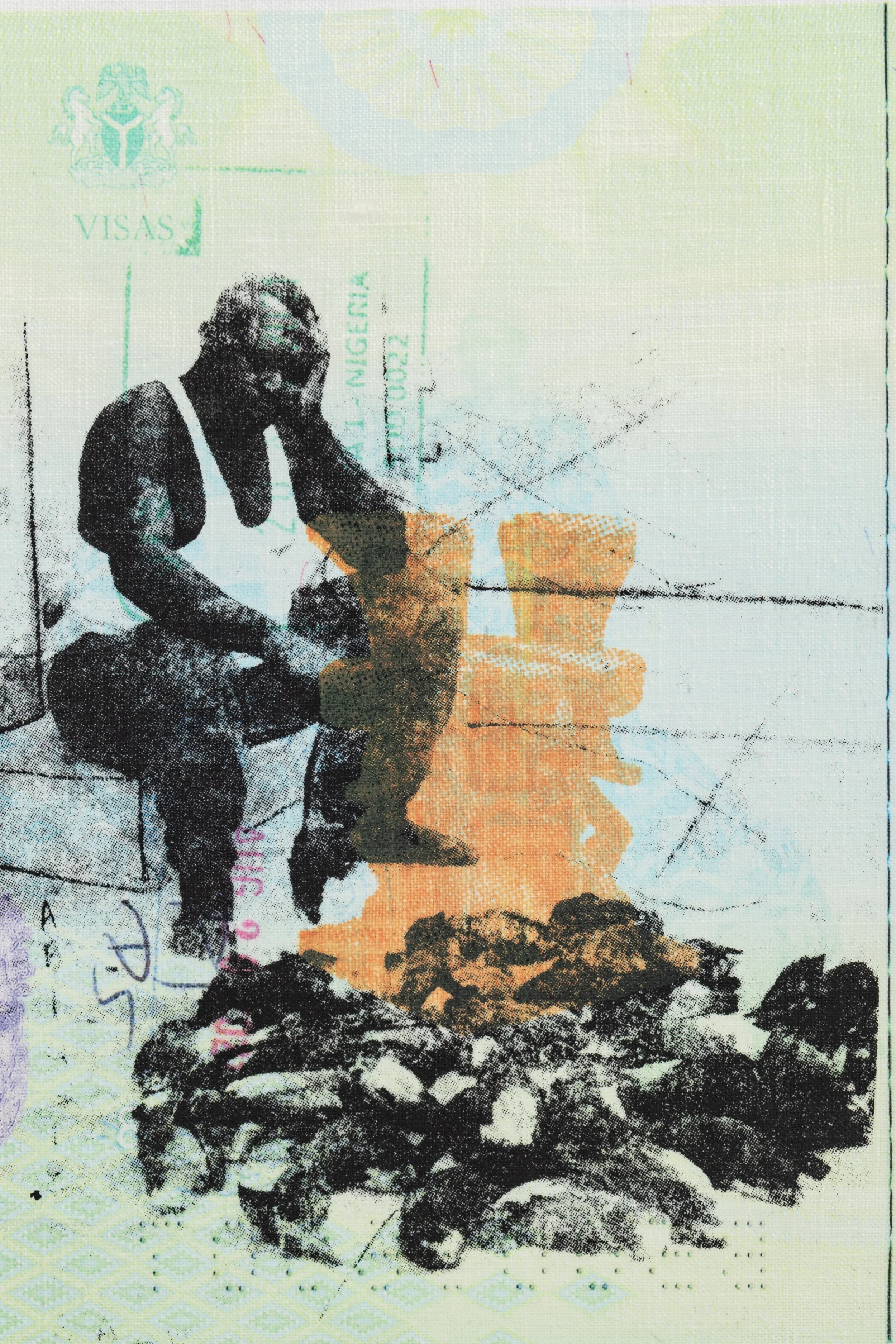

Benita Nnenna Nnachortam, Journey of the bird (I), 2024

Rebecca Fowke, Mother, 2023

Yasmin Essafi, Summers, 2024

Rebecca Fowke, Nganga

Yasmin Essafi, Afternoon Rain, 2024

Rebecca Fowke, Dinka Ananda, 2024

Yasmin Essafi, All That is Left, 2024

Kwadwo Adae, XXXIV, 2011

Zajah Divine, Her Image

On View October 9, 2025 - January 9, 2026

Featuring artworks by Kwadwo Adae, Zajah Divine, Yasmin Essafi, Rebecca Fowke, Louise Mandumbwa, and Benita Nnachortam, Liminal Landscapes showcases artworks that consider the nuances and complexities of diasporic life. By qualifying the often vast distances between home and homeland–daily life and nostalgic memories–Liminal Landscapes grieves what’s been left behind and envisions futures yet to materialize, while reveling in the sites of liminality, or transition, that bridge the two. And, by leaning into these tensions, the exhibition also invites viewers to position themselves amidst highly charged landscapes of remembering, reckoning, and transformation.

Across the exhibition, Connecticut-based artists of African origin or descent consider how histories of migration and displacement, legacies of slavery, and tenets of globalization reverberate against the immigrant experience in America today. Through the experimental use of photography, painting, printmaking, and assemblage, they embrace modes of production that welcome fluidity and disorder, allowing for intricately layered depictions of diaspora that visualize the intangible inbetweeness of diasporic life.

In her three mixed media works on view, Rebecca Fowke–a Zimbabwean-American, New London-based artist–investigates diasporic identity through, “paying tribute to [her] birth home, the land of [her] mother, and her ancestor’s ancestral lineage.” In Mother, Fowke draws upon early memories of Zimbabwean mothers working multiple jobs to provide for their children, sending earnings home from distant cities or foreign countries. Here, the mother figure is adorned with a crown and necklace symbolizing her status as a sacred conduit of knowledge and wisdom. Her breasts are rendered as the feet she walks upon, personifying the liminal, plural, and often invisible nature of women’s work. In Nganga, Fowke uses clay, beads, paint, and ephemera to visualize the spiritual quality of the liminal space between mind, body, and soul. The term refers to a traditional healer or spiritualist who heals both physical and emotional wounds in communication with ancestral spirits. Fowke shares that both her grandmother and mother went through initiation, but were ultimately not drawn to the path. They instead chose to hold conversational and therapeutic space for people, which the artist illustrates through the two adjoined faces in the work which, more broadly, celebrates the roots and threads that connect us all.

Louise Mandumbwa–a multidisciplinary artist from Botswana who currently calls New Haven home–makes work that engages collective memory and personal history to fill what she terms, “the gaps in knowledge that are often part of a diasporic experience.” As the daughter and granddaughter of intra-continental immigrants from Zambia, Angola, and the Congo, her works often ask what and where is home? In addressing this personal yet universal diasporic concern, she turns to familial archives and her own memories for tangible effects from the places she’s called home. Her canvases play with what is perceptible and imperceptible about these memories; they toggle between macroscopic landscape and microscopic detail, the figurative and the abstract. For Mandumbwa, unlike human memory, the land holds irrefutable evidence, a truth embodied in Configuration 1, where she visualizes her enduring yet fragmented image of her grandmother’s garden. Here, the artist depicts sugar cane–across two adjoining canvases of varying opacities–to honor the labor of her matriarchs’ hands while also recalling fleeting moments of sweetness and rest. For Mandumbwa, “mapping nodes of connection across time and space–and placing presence, absence, and approximation in conversation–offers a more honest context of a moment or place than a totalizing image.”

Benita Nnachortam–a Nigerian artist of Igbo tribal origins who’s called New Haven home for the past few years–adopts a mixed-media approach in excavating the lasting imprints of globalization on African peoples and cultures. Questions central to her practice include: What is the fate of our collective Neo-History as Anam, Igbo, Nigerian, or African people in today’s world? What institutions preserve these histories, and how can artists exhibit or incubate our cultures before they fade? Through these questions, Nnachortam names the responsibility of art and artists to hold histories and cultures at risk of erasure, while activating her own artworks as living archives that preserve the interwoven layers of collective memory, history, and identity. Her dynamic compositions fuse together familial photographs, symbolic cyanotypes, hand stitched embroidery, painting, drawing, and screenprinting to embody what the artist terms the, “tension between traditional heritage and contemporary life.” This tension is embodied in Journey of the Bird (I), where Nnachortam depicts a Nigerian man seated on a stoop, gazing defeatedly upon a pile of dead birds that, “passed in transit—a failed mission for an Igbo tradesman.” The work’s background depicts translucent overlays of passport pages and visa stamps to evoke the bureaucracy of human travel across invented borders, while its title conjures visions of the mythological Phoenix rising from its ashes, or the Sankofa bird as it reaches back across the liminality of time for wisdom and understanding.

In XI and XV, Kwadwo Adae–a local artist of Ghanaian descent, perhaps most celebrated for his figurative, public murals–uses abstraction to transform ancient Adinkra symbols and Kente cloth patterns into a visual critique of contemporary American politics. He states, “Rather than offering a neat, idealized version of our current chaotic reality, non-objective art communicates a fragmented, unsettled reflection of the disorder and confusion that fascism creates.” In his use of ancient cultural iconography that pre-dates the emergence of fascism by over three-hundred years, Adae laughs in the face of the establishment, exposing the limits of structural power in its ongoing attempts at cultural erasure. And, by revisiting symbols used by the Akan people in death ceremonies and other rituals marking the transition from one state of being to another, Adae also celebrates liminality as a site where eternal power is generated through processes of radical transformation. In XI–the first painting Adae completed after graduate school, where the administration continually questioned his artistic talents–Adae marks his own transition through the liminal space between the pain and doubt of that experience and the healing and confidence it took to then open his own art school. An educator by nature, Adae is more interested in the viewer’s interpretation of an artwork than his own motivations and stories behind its creation.

Zajah Divine–a Bridgeport-based artist of Jamaican descent–uses art to, “navigate the chaos of faith and self-discovery, and heal the soul.” For her, wandering is a strategy to both know oneself and navigate the darkness of unknowing that typically characterizes liminal spaces. The artist’s statement reads as both poem and affirmation: “Her eyes reflect the art of a wandering soul, Seeking the light in one's own identity, In her shadows, For every strong tree plants its roots in darkness, For every seed must find the light to grow…” This underlying theme of embracing uncertainty to achieve enlightenment and growth is mirrored in Divine’s chosen medium; the intaglio print. Her striking, monochromatic prints, Her Image and Her Imagination, are produced through an intensely hands-on process where she carves grooves into a plate to form a negative image, applies ink to the incisions, and reveals a positive image by using a press to transfer ink to paper. Here, she both literally and figuratively infuses liminal space with meaning, using inky layers to reveal the intricacies of diasporic identity, while also obfuscating the traditional gaze that aims to objectify and subsume it.

Yasmin Essafi–an American photographer of Moroccan descent who currently lives between Connecticut and Nairobi–presents four striking photographs from a recent series titled, "In the Wake of Time," which captures the “fluidity of memory, history, and daily life in Cuba.” Through her expert use of sharp contrasts and blurred motion, Essafi produces nostalgic, somewhat haunting, images that reflect a country, “in constant negotiation with its past and present.” She illuminates the liminal spaces between then and now, origin and destination, and presence and absence, exposing–often within a single image–just how blurred those distinctions can be. A traveller by nature, Essafi is interested in how the ephemeral yet persistent nature of time defines the relationship between people and place—“how it lingers, erases, and transforms.” Instead of endeavoring to capture what she objectively observes of cultures that do not belong to her, Essafi instead channels what she subjectively feels in the moment the photograph is taken; “the echoes of history, the weight of the present, and the fleeting nature of both.” In Afternoon Rain, a woman walks through the rain, lugging a rolling suitcase behind her with one hand and holding her umbrella above her head with the other. The scene reminds us that, like time itself, the storm always passes, and that the joy of arrival often eclipses one’s memory of the arduousness of the journey.

Together, Kwadwo Adae, Zajah Divine, Yasmin Essafi, Rebecca Fowke, Louise Mandumbwa, and Benita Nnachortam dare to envision worlds defined by interconnectedness, even, and perhaps especially, across geographical distance and cultural difference. By mobilizing art as a tool to both visualize and harness the transformative power of liminal space, Liminal Landscapes offers viewers glimpses into a future, where identity is self-defined and notions of home and belonging are self-determined.

— nico w. okoro, Curator-at-Large, Orchid Gallery | Founding CEO, The Building Fund

Liminal Landscapes is Orchid Gallery’s third exhibition curated by nico w. okoro from the 2025 Open Call, and is on view at Orchid Gallery through January, 2026. The Opening Reception runs from 6-8pm on Thursday October 9th, and includes an Artist Talk/Q&A between 6:30-7:30pm.