Odette Chavez-Mayo, Kali

Merik Goma, As I Wait, Untitled 11

Brock Bowen, A Touch of Creativity; Green

Tazje Henry-Phillip, Pear for Your Thoughts, 2025

Odette Chavez-Mayo, Inanna

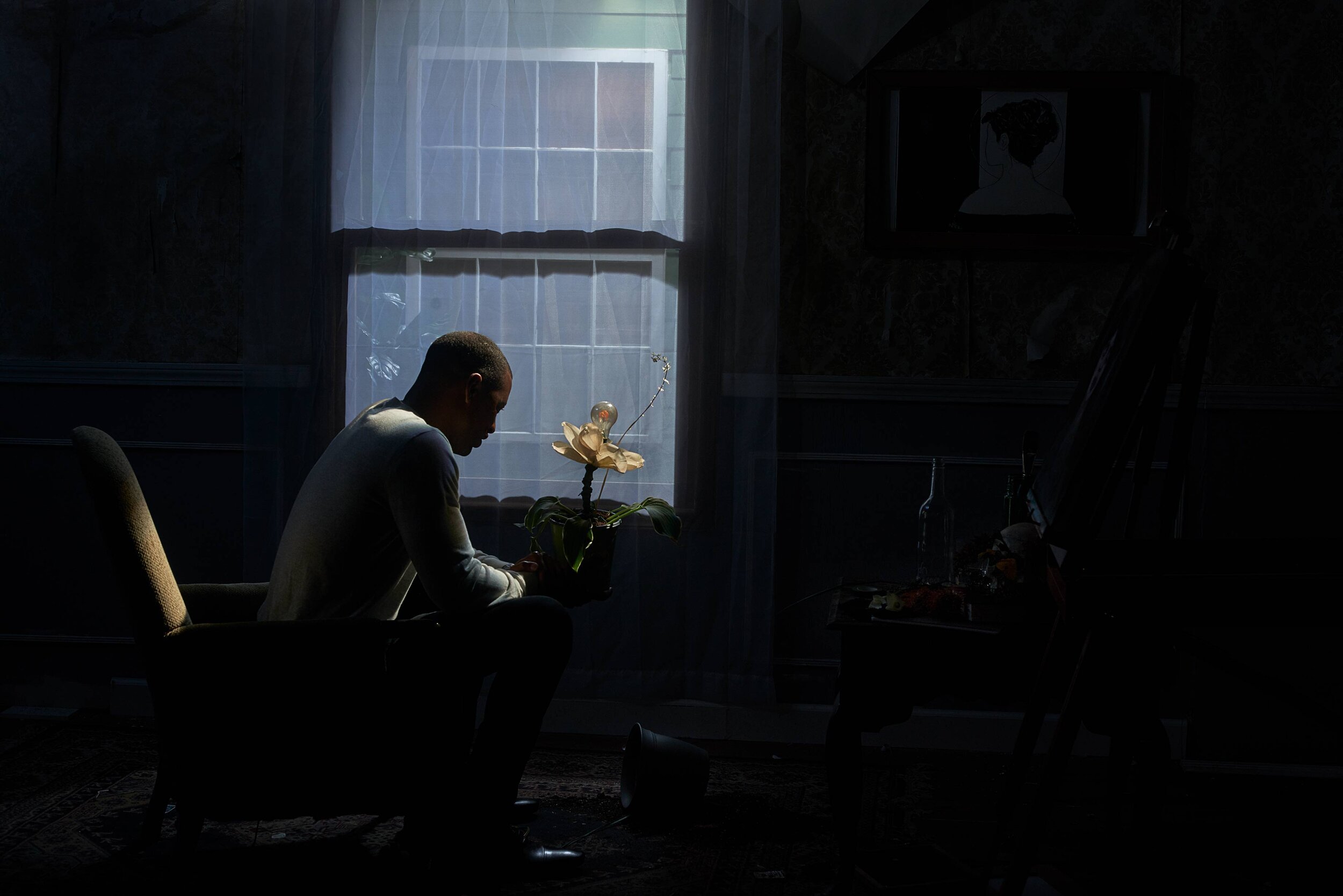

Merik Goma, Theater

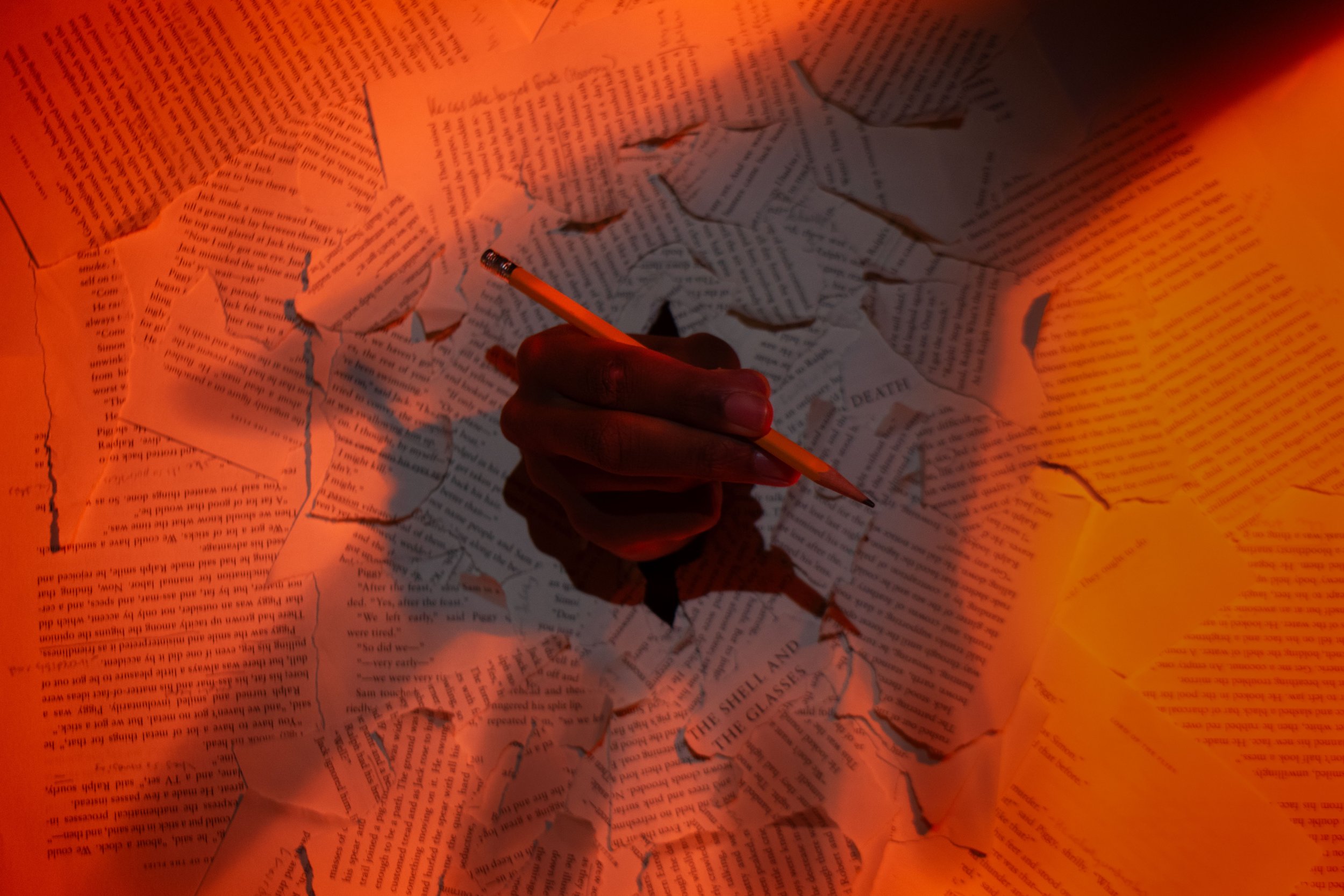

Brock Bowen, A Touch of Creativity; Red

Tazje Henry-Phillip, Still Life #2

Odette Chavez-Mayo, Tu Mano

Merik Goma, In This Light or That Light

Brock Bowen, Preservation; Safekeeping

Tazje Henry-Phillip, Little Violin, 2017

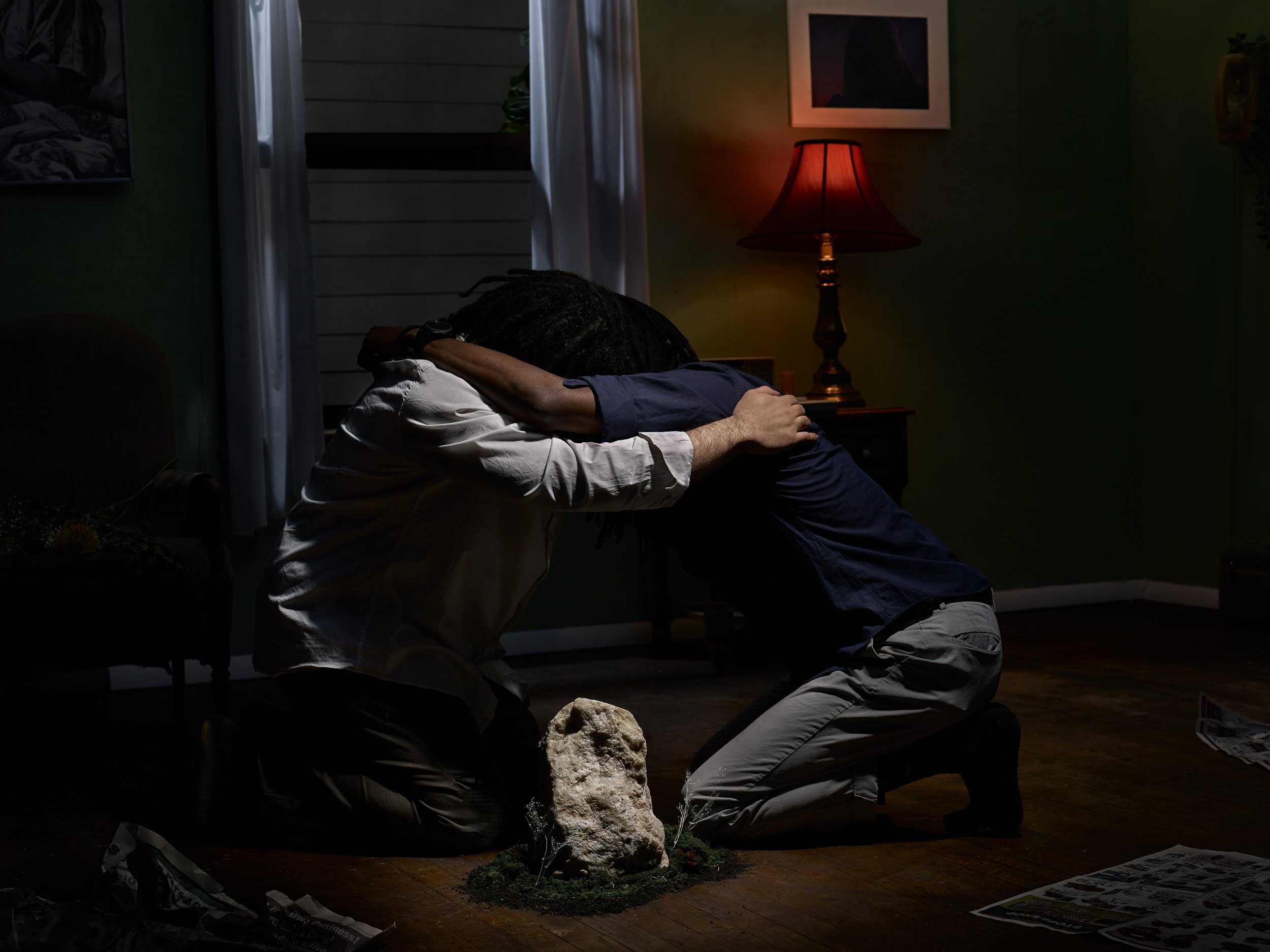

Merik Goma, Your Absence is My Monument Untitled 1, 2020

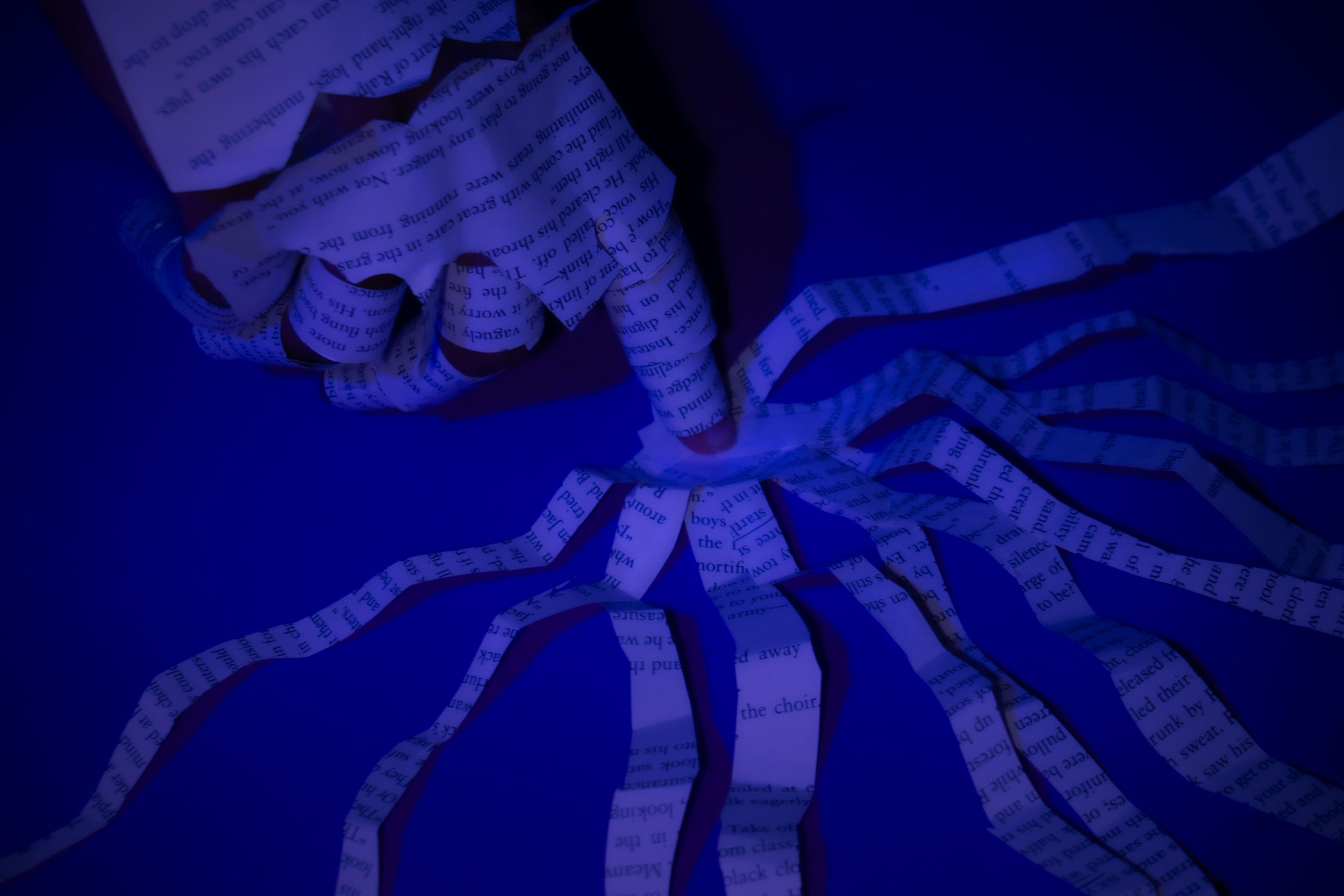

Brock Bowen, A Touch of Creativity; Blue

Merik Goma, Chasing Light

Odette Chavez-Mayo, Mi Mano

On View April 10, 2025 - July 3, 2025

In Our Hands showcases artworks that consider the role hands play in identity formation, self-expression, and worldbuilding. Within an art context, the artist’s hand boldly produces culture, often shaping intangible ideas into tangible art objects. Within a broader context, hands shape our daily lives; they construct, animate, and destroy worlds on a spectrum of scale and visibility. Brock Bowen, Odette Chavez-Mayo, Merik Goma, and Tazje Henry-Phillip mobilize this immense power, engaging hands—or the traces they leave behind—as a visual storytelling device. For them, hands are both medium and message; they reveal clues about one’s rich inner life, while also communicating a great deal about how one navigates the exterior world. If eyes are windows to the soul, then hands—with their infinite actions and gestures—are windows to human agency, where mind and body meet through the will to act.

Brock Bowen and Odette Chavez-Mayo boldly position their own hands as protagonists within their remarkably lyrical photographs. Bowen—the first local high school student to exhibit at Orchid Gallery—explores, “paper as a mode of self-expression, illustrating how the medium can be used to morph a person's image, as a catalyst for creativity, and as a way to preserve memories and experiences.” Cast in blue, green, and red light, his A Touch of Creativity series depicts dramatically staged scenes where paper and flesh meet, the paper carrying written messages and the hand carrying messages coded in its gestures. Bowen’s expert manipulation of light and shadow produces striking visual narratives that are at once autobiographical yet open to the viewer’s interpretation.

Chavez-Mayo is a photographer whose nostalgic black and white images—each of which is staged in nature and radiates soft, natural light—explore the contours of memory and her longing for her Mexican homeland. She, like Bowen, experiments with placing her own body in her work as a conduit between past and present. However, her works also carry the artist’s hand in a different way; through the laborious practice of developing images in the darkroom. Chavez-Mayo states, “central to my photographic practice is working with processes that take time. I use analog film and enjoy the physicality of making pictures come to life by laboring in the dark(room).” For her, the process of developing film is synchronous with the process of developing a sense of self or other, as filtered through the hazy lens of memory. In Inanna, Chavez-Mayo offers a powerful self-portrait, where the full depths of her photographic process and explorations of identity are quite literally laid bare.

Whereas Bowen and Chavez-Mayo cast hands front and center as lead actors in their energizing works, Merik Goma and Tazje Henry-Phillip present scenes of radical rest, where hands are imagined, or their gestures depicted only as traces. These still lifes—or artist-constructed compositions that communicate meaning through the arrangement of objects—instead ask viewers to tap into their own creativity and envision the protagonists that might animate said objects. In Chasing Light and In This Light or That Light, Goma prompts us to picture a person at rest through his arrangement of six simple objects; a lamp, chair, desk, cup, flowers, and books. While the hand is not present, its trace remains and its assumed role within the scene is palpable. In Theater, viewers find themselves lost in their own thoughts as they try to locate the faint, eerie handprint on the velvet curtain in the upper lefthand corner of the composition. In his portraits, however—one which depicts a man holding a dying plant out of which a light bulb and fake plant blooms, and the other which depicts two men locked in a firm embrace—Goma reveals his process. He states, “I construct sets that the work inhabits and transform the space to create new narratives—they are intended to engage the viewer in their own personal dialogues and histories.” By daring viewers to cast themselves as main characters within the highly cinematic worlds he creates, Goma explores how we project our worldviews onto others, offering sharp observations of our psychological and social interconnectedness.

Like Goma, Henry-Phillip also engages the still life as a site for bridging contemporary ways of seeing with classical modes of artistic expression. While the origin of still life painting is often attributed to the Netherlands in the early 1600s, the practice actually dates back to Ancient Egypt, where still life cave paintings functioned as both offerings to the gods and talismans to accompany the dead in the afterlife. Henry-Phillip harnesses these spiritual origins of the artform, stating, “I create art that feels expressive. My hope is to make distinctive and captivating works that evoke emotion and enhance environments.” In her acrylic and oil paintings, the overwhelming emotion is calm and the environments themselves conjure a delightfully sleepy Sunday afternoon. Deceptively simple in their compositions, Little Violin and Still Life #2 prompt viewers to envision the person whose hands would make music, sip coffee, lather soap, or engage in other forms of leisure and self-care.

Across the exhibition, certain symbols emerge—flowers and cups symbolizing abundance, books and lamps symbolizing enlightenment, and of course hands symbolizing humanity and a wide spectrum of human emotion. In Our Hands honors the courage it takes to build and find beauty in an increasingly ugly world, while celebrating a generation of artists bravely reaching. Whether it's grasping back nostalgically into the annals of memory and history, or stretching expansively into the rich depths of one’s own consciousness and imagination, these artworks affirm the adage that the future is in our hands.

- nico w. okoro, Founding CEO, The Building Fund | Founding Partner + Curator-at-Large, Orchid Gallery